781 Per Day

Grieving is a highly personal experience. When I worked in the U.S. Senate at the height of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, I had the solemn privilege of attending several funerals for fallen American service members at Arlington National Cemetery. For all of the precision and uniformity of a military ceremony, each funeral, each graveside service, was different—reflecting the wishes of family or the fallen heroes themselves. The one constant was that each was unbearably sad.

In the eight years of the Iraq War (2003-2011), the United States lost 4,497 service members. That’s about 2 deaths per day in that war alone. In World War II, an average of 297 Americans died on each day of the war. In America’s most deadly war, our Civil War, the rate of death for Americans on both sides of the battle was about 520 deaths per day. But in the 128 days since the first case of COVID-19 was confirmed in the United States (January 21, 2020), more than 100,000 Americans have died—that’s an average of 781 deaths each day for more than 4 months.

In today’s media environment, we can stare at a fixed point with surgical precision 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, 365 days a year. Reporters will camp outside a Congressional witness’ home for days or even weeks to grab footage of the person in the limelight. Media can bring us together to grieve for one person with reverence and poignancy, peeling back the layers of meaning in an individual’s life. And media can help us grieve in mass casualty events—such as after Sandy Hook or Charleston or even 9/11.

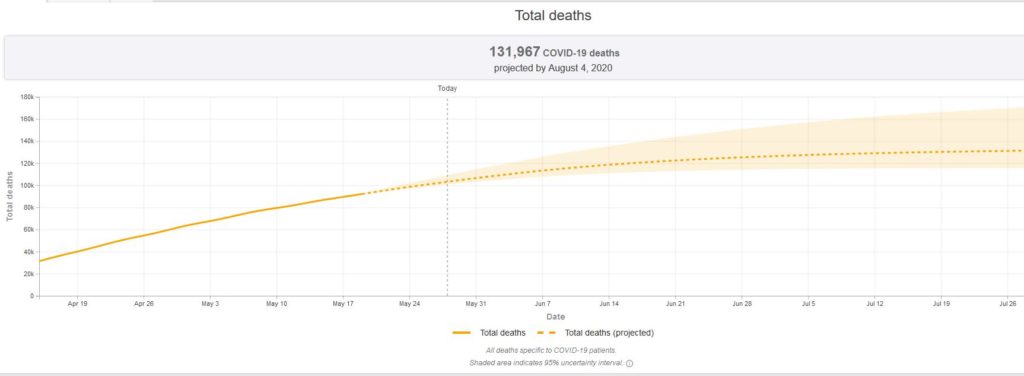

But today’s media—both broadcast and print—is ill equipped to report on the 781 lives lost each day over the last four months. Even before local newsrooms started hemorrhaging jobs and reporters, the sheer volume of death makes that kind of hyper-local reporting impossible to do on a national scale. There just aren’t enough reporters or column-inches. As a result, there is no single repository of memories of those lost to COVID-19. There is no “Faces of the Fallen” for people struck down by this virus. There is no opportunity for us to grieve and remember, collectively, our fellow-citizens. There are, instead, the most impersonal statistics about infections and deaths all expressed in line graphs.

It’s here that leadership matters.

In this moment, we need leaders who will lead: in our mourning; in our grieving; and ultimately, in our healing. Leaders shouldn’t be so afraid of the virus that they ignore or gloss over the frightful human toll it has taken on on our country, on 100,000 families, on thousands of communities. We need leaders to help us find meaning in all of this loss, to buoy our resolve for the difficult challenges that still lie ahead. We need leaders to tell families and friends of all those who have died that this great nation mourns with you.

At some point, we will have a conversation about the Trump administration’s response to the pandemic. We’ll debate whether their actions were sufficient. We’ll argue over whether there was more that could have been done—that should have been done.

But for now, I’d be content for a leader to emerge who understands that in this moment we need someone who will walk with us through the challenges of life. Who willingly leaps into the trenches with us when the fighting is dirty and the loss weighs heavy on our souls.

The most searing memory I have of the funerals I attended at Arlington was for a soldier whose wife found in his death more pain than she could bear. I recall her standing in the sunlight that day, her shoulders heaving with each sob, and hoping she knew that she wasn’t alone in her grief. Assembled on the grass in section 60 of the cemetery that day were two U.S. Senators, several generals, chaplains, honor guards, family members, friends, and others. We did not all know her or her husband, but we were all there to show our respect and to offer comfort, even if it was with nothing more than our presence.

With a virus that makes in-person, collective mourning impossible, now more than ever we need leaders who can bring us together to mourn as a nation; to stand shoulder-to-shoulder, as one people; to remind us that love is real; and that, yes, we will get through this together.