Democracy in Peril

When I moved back to New England eight years ago, the state of Rhode Island was in tough financial shape and several municipalities were being administered by officials appointed by the governor. Let’s be clear about what this meant: whole communities—and sizable ones at that—had local democracy subverted and replaced by appointed officials. I was troubled by the phenomenon. It struck me as running counter to so many of the ideals and myths about America that cut to the very core of our identity. I did some preliminary research to try to figure out how extensive a phenomenon it was nationwide. The answer: more extensive than you might believe.

In fact, it was a similar set of circumstances that led to the water crisis in Flint, Michigan. Because of the crumbling finances of the city of Flint, then-Michigan Governor Rick Snyder appointed an “emergency manager” who took charge of Flint’s finances and determined to save municipal money by terminating Flint’s relationship with the Detroit water authority, and instead using water from the Flint River. The Flint River water, however, was not treated with corrosion control chemicals and ate through the old pipes at the heart of that once-mighty industrial city. The resulting corrosion put lead into the water of Flint—lead, perhaps the best understood neurotoxin. Exposing young brains to lead is to sentence those souls to cognitive decline. It changes lives for the worse. Flint became a full-fledged public health crisis.

In Flint, people new something was wrong. Despite reassurances from state and local officials, the water tasted odd. It looked worse. But the person making the decisions at that time wasn’t accountable to the people of Flint. He was accountable to the governor of Michigan, and that is one of the dangers of setting aside democracy: when the people don’t matter, their voices aren’t heard.

It took a remarkable coalition, including a crusading pediatrician, a water scientist, and local activists to reverse what was going very wrong in Flint. But for me, this is a story about disenfranchising Americans—about diminishing, devaluing, or eliminating the power of people’s votes.

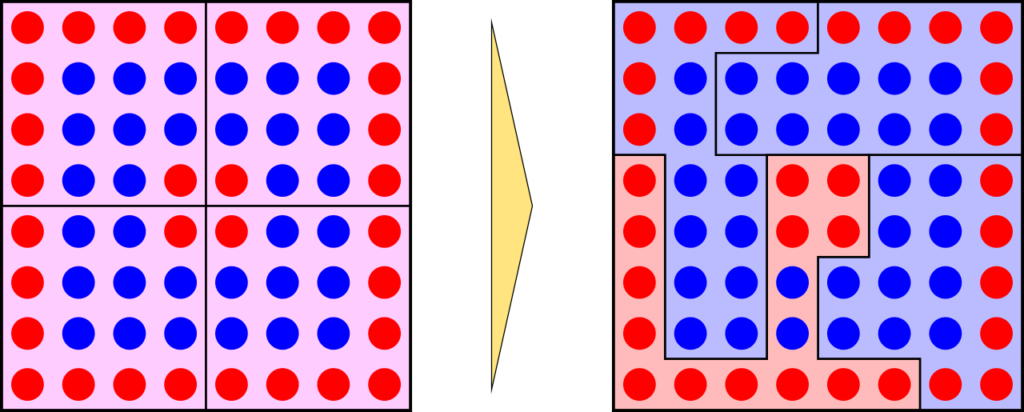

The alarming truth is that there are efforts to diminish the power of democracy happening all over the United States. We see evidence that people want to resurrect poll taxes, and literacy tests. In some cases, the efforts to disenfranchise voters takes the form of how many polling machines you put in a given voting precinct. Every case of gerrymandering you hear about is an effort to concentrate blocs of voters into as few Congressional districts as possible, often by race. Cases in North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Ohio, and Michigan have either been settled in the courts, or will be, but all raise profound and troubling questions about the commitment of many American political leaders to the very meaning of democracy.

I think we have to keep an open mind, too, about whether the loss of suffrage due to criminal conviction isn’t, itself, a type of structural disenfranchisement. We know that African Americans and Hispanics make up only 32% of the country’s population; but they make up 56% of the prison population. When they get out, if they’ve been convicted of a felony, they won’t be able to vote in most states. The end result is a large segment of the American population—many of whom are from under-represented communities—who can’t vote; and whose voices are effectively eliminated from the American public square.

I am of the view that American democracy is strongest when every voice has an equal chance to be heard. We should be looking for ways to make participation in the political process easier; not harder. We should be helping Americans vote in races that are meaningful and consequential. Democracy is not just about who won; it’s about discerning the consent of the governed. We compromise that at our own peril.