Citizens Must Be Sophisticated Consumers of News

“There’s No Way to Report Many of the Fastest-Spreading Las Vegas Conspiracy Theories on Faceebook” | Quartz

“Facebook and Google Pledged to Stop Fake News. So Why Did They Promote Las Vegas-shooting Hoaxes?” | Los Angeles Times

“Russia’s Hybrid Warriors Got the White House. Now They’re Coming for America’s Town Halls” | Foreign Policy

“These are the Facebook Posts Russia Used to Undermine Hillary Clinton’s Campaign | Think Progress

“Fake news” is more than just the domain of Russian influence operations. It’s a permanent part of the media landscape—and it has been for millennia. You can think of heresy in the early Catholic Church as a form of “fake news.” You can think of the yellow journalism that took the United States to war against Spain at the end of the 19th century as a more recent example. In today’s media environment, there are those who trade in fake news as a way to attract viewers and advertisers. Characters like Alex Jones of Info Wars stand out, but he is not the first infotainment charlatan, and he’s likely not the last.

The challenge for citizens in democratic societies is to distinguish reliably between legitimate news—things we need to know and understand in order to shape our societal response—from fake news—stories that serve some other purpose, from profit to corrupt influence.

In the aftermath of this week’s horrific massacre in Las Vegas, we saw disinformation rear its ugly head. Facebook and Google promoted links to known-conspiracy peddlers that were completely devoid of fact about who the shooter was and what his motive might have been. In some respects, it’s understandable. In the heat of breaking news, any explanation feels grounding—particularly if it serves to confirm our worst fears and biases. But that’s precisely when citizens need to stop, gather more information, and think. An example from history illustrates our task:

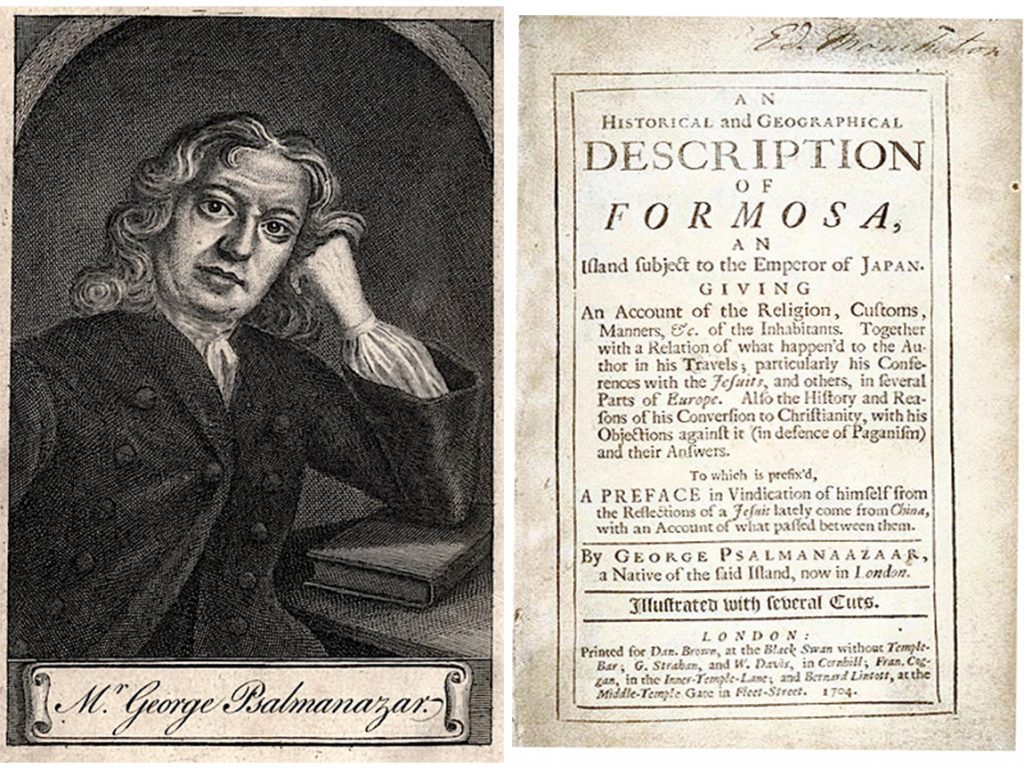

In the early 18th century, a fair-haired, blue-eyed man appeared in London going by the name of George Psalmanazar. He claimed to be the first-native born person from Formosa (now, Taiwan) to travel to Europe. He claimed to have been abducted by an evil Jesuit priest and brought forcibly to France where they tried to convert him to Catholicism. He refused and escaped, only to be captured by Calvinists who tried to convert him. Again, he refused their efforts to convert him and escaped—or so Psalmanazar claimed. Upon arriving in London his stories of abuse, especially at the hands of the Jesuits, played to the confirmation bias of his audience who distrusted Catholics and disliked Catholicism.

Many of Psalmanazar’s claims just didn’t add up. First off, blonde-haired and blue eyed, he didn’t look Asian. His stories of barbaric practices—the ritual sacrifice of 18,000 boys under the age of 9 every year—didn’t seem plausible given what was known about the size of the population on Formosa. He was called to account before the Royal Society—where the most educated people in the 18th century came to share their latest data-driven understanding of the world around them. They questioned Psalmanazar. Sir Edmund Halley (famous for Halley’s Comet) asked all manner of precise questions about astronomical observations from Formosa.

Psalmanazar was a gifted storyteller and could definitely think on his feet. He continued to fool some, but then the information networks of the late 17th and early 18th centuries began to produce results that undermined Psalmanazer’s claims. The head of the Royal Society was none other than Sir Isaac Newton. Not just a genius of the scientific sense, he was an early super-user of information networks. He was a share holder in a number of joint-stock companies trading around the world. He held position in government. He was at the hub of a vast network of information that moved by letter, by journal, and by report back to headquarters in Western Europe. Together, the input from all of these networks served to undermine the credibility of George Psalmanazar who died in relative obscurity an admitted fraud.

The take-away for the current consumer of information is one of hope and one of imperative. The Enlightenment in Europe is rightfully celebrated as the awakening of reason in public life. Science, data, and reason supplanted faith and orthodoxy. There remained much to learn about the physical world and progress would take centuries to achieve, but there is hope in the fact that perhaps our era is not so flawed if the age of Sir Isaac Newton suffered the intellectual insult of a George Psalmanazar.

The imperative to the contemporary citizen is that we, as consumers of information, must do what the Royal Society did in the early 18th century:

- Challenge assertions. Ask yourself—how can I confirm what I’m reading? In 1704, that meant writing letters and waiting weeks and months for a response. Today, we can google it.

- Ask: is anyone else reporting it? If something is a big explosive story, then it’s not only going to be covered by a news outlet you’ve never heard of before. Again, google it. Is anyone reputable covering it? If not, maybe wait a couple of hours before you share it, Tweet it, or forward it.

- Ask: would the person or organization making such claims be in a position to actually know the facts they are reporting? Journalists at major news outlets, in particular, spend years and years cultivating sources. It’s unlikely someone you’ve never heard of before at a previously non-existent news outlet scooped them. In George Psalmanazar’s case, the suggestion that he was a native born Formosan, with blue eyes, fair skin, and blonde hair, seems like it should have been a tell that he wasn’t being honest. There are similar tells today.

- Finally, ask: do the circumstances around the news play to confirmation bias? Psalmanazar got as far as he did, in part, because he arrived in London with a story that blamed Catholics and Jesuits in particular. Stories of their wicked ways were expected in early modern England, and Psalmanazar found a receptive audience then just as comparable stories about Muslims do today—not because the stories are true, but because they confirm the bias of their audience members.

The best antidote to fake news is an informed, critical-thinking citizenry. The information tools at our disposal today are staggeringly vast in their reach and miraculously fast compared to the correspondences that informed the Enlightenment. But we must choose to be better consumers of and purveyors of information. Our task isn’t anything more complex than making a conscious assessment about the information we share in our own networks and demanding the same from our friends and followers. The tools are there. We just have to use them.