Back to the Future

Every four years we have a presidential election that sets the agenda for the country for the following four years. Theoretically, the election is the culminating moment of a national dialogue. In the ideal, the vote is an expression of the nation’s opinion, not necessarily on the fitness of candidates, but on the major issues of the day.

Growing up, I loved campaigns because of that Capra-esque idealism. I reveled in the belief that as a nation, we had an opportunity to choose between two different visions for moving the country forward. The direction didn’t seem in doubt. Elections seemed to be more about how to get things done—not whether.

In those days, I loved the skill of impassioned argument. I used to watch, with rapt attention, former California Congressman Bob Dornan give speeches on the House floor about freedom in Latin America, about the struggle between the United States and the Soviet Union, about the promise of American exceptionalism. I used to argue with my friends at the lunch table about funding the Contras. I can remember debating with classmates about arms control and the need for a nuclear deterrent.

I was a good Cold Warrior in the 1980s. I know I wasn’t a typical teenager, and maybe my friends weren’t typical either. But they were my friends. Even when we disagreed on fundamental of issues, we didn’t stop being friends. I never questioned their intelligence—in fact, I relied on it. As I crafted my most sophisticated arguments about the struggle between East and West, I put my faith in their good faith arguments. I put my faith in their reasonableness. I put my faith in their intelligence. In fact I feared it. What if they knew something I didn’t know? What if they were smarter than me?

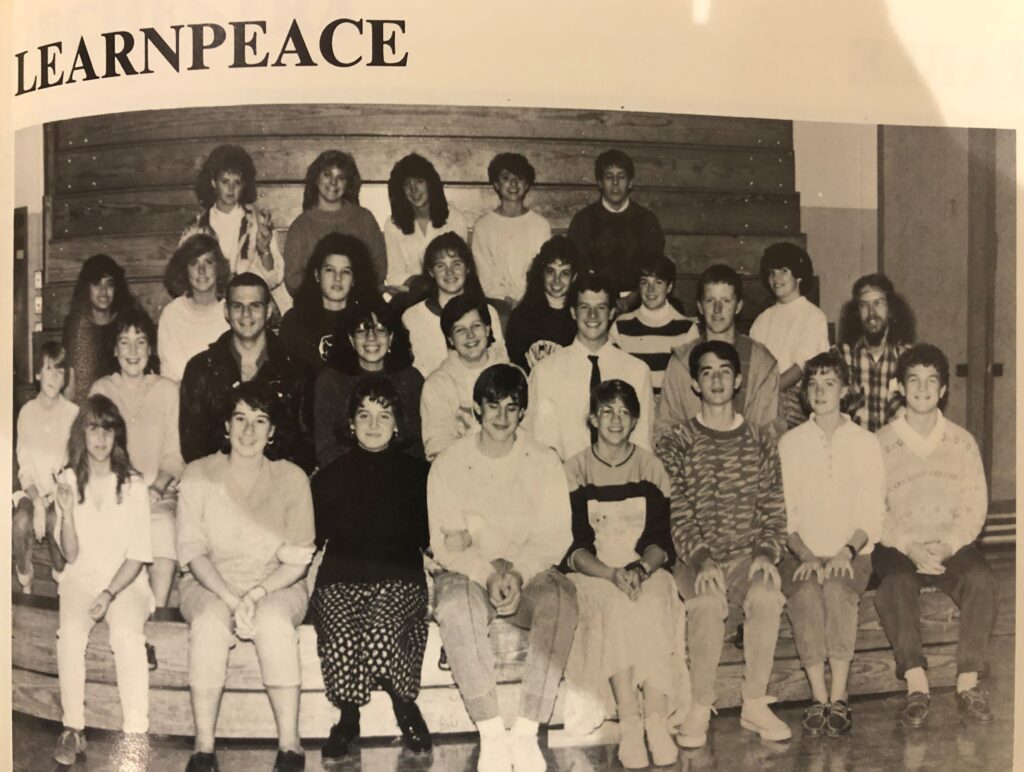

Those debates at drama club, in empty-classrooms after school, and in the parking lot of our favorite ice-cream place drove me to read, to want to know more about the world, and to be better informed so that I could hold my own in those debates with my friends.

I wish tonight’s debate held out the promise of such idealism.

But American politics isn’t a Frank Capra film. Hell, it’s not even an Aaron Sorkin screenplay. Today it seems more like a middle-school drama club production, with less sophisticated dialogue.

Still, in the pitting of ideas against each other, there is hope. On Friday, I’m going to moderate an issue forum between the College Republicans and the College Democrats in my day job at Salve Regina University. These students have been preparing for it for weeks. Interest on campus is high—even amidst mid-term exams and all the pandemic-stress. My expectation is that both the College Democrats and the College Republicans will prepare seriously for this forum—at the very least mindful of not wanting to be publicly bested by their counterparts. I hope they have read their rivals’ positions, developed arguments for and against key proposals—on both sides, and generally immersed themselves in the issues they are debating.

I don’t expect these students to find common ground, but I do hope that in preparing for this debate, they might learn something new about their opponents’ concerns. I know I did in my school-age debates and it helped educate me.

When I got to work professionally at the intersection of politics and policy, I carved out a reputation as a non-interventionist defense hawk. (I didn’t think the United States was well-served by military intervention, but when military action was necessary I wanted it to be overwhelming.) My friends at the lunch table would probably still disagree with me, but they helped shape my thinking. They helped challenge my assumptions. They made me work harder. Most of all, they taught me that intelligent people can disagree about complex issues.

We need rivals in life to challenge us and to spur us onward. But for that to happen, we can’t view our rivals as uneducated or unprincipled. We have to believe that from them there is something worth learning.