It’s Not a Constitutional Crisis

It’s easy right now to let our worries and anxieties about events in Washington consume us. A quick listen to the talking heads or a glance at some of the opinion pages would lead you to believe that we’re in the midst of a full-blown constitutional crisis. It’s a thought that I’ve considered on more than one occasion in recent months, largely stemming from the proliferation of congressional investigations into the conduct of the president and the president’s efforts to actively resist those investigations. But cries of crisis are, as of this writing, premature.

We’re witnessing a test of wills and power between the legislative and executive branches of government. The leadership in the House of Representatives has opened (or breathed new life into) investigations of Russia’s attack on American democracy in 2016; the lending practices of Deutsche Bank—one of the major financial partners of the Trump Organization; the issuance of security clearances in the White House; the president’s personal finances; and, of course the Mueller report, among many others.

In each of these cases, the president, his company, and/or his administration are resisting Congressional authority:

- Deutsch Bank: earlier this week, the Trump Organization filed suit against Deutsch Bank and CapitalOne to block them from complying with Congressional subpoenas that may reveal financial details about the president and his business.

- Security Clearances: while Carl Kline, the former head of the White House Presidential Personnel Office, testified behind closed doors on Wednesday about the security clearance practices of the Trump White House, the administration has thus far refused to comply with a request for documents in the matter.

- Personal Finances: the House Ways and Means Committee requested 6 years of the president’s tax returns. The Treasury Department has so far failed to meet two deadlines to turn the documents over to Congress.

- The Mueller Report: while Attorney General William Barr testified to the Senate Judiciary Committee on Wednesday about the Mueller report, he is refusing to testify to the House Judiciary Committee and the Justice Department is refusing to turn over the full, un-redacted Mueller report and its underlying evidence. Furthermore, the White House has indicated it will resist any effort by Congress to interview former White House Counsel Don McGhan whose testimony to Special Counsel Robert Mueller is among the most incriminating parts of the Mueller report.

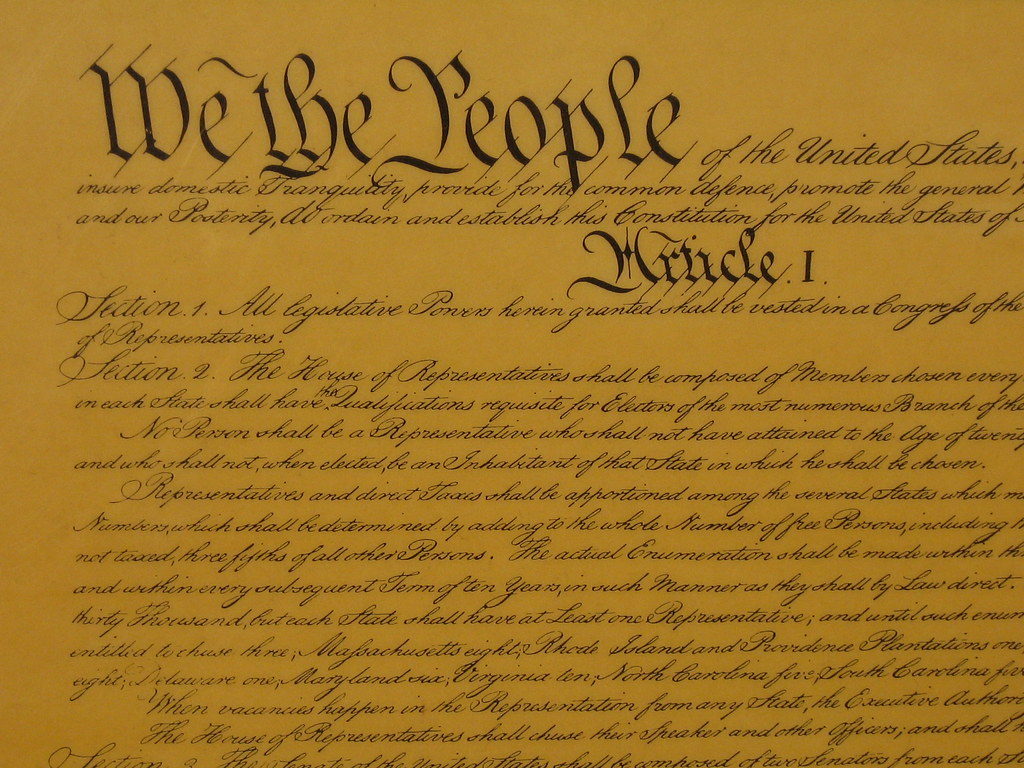

A week ago, President Trump proclaimed his administration would resist all of Congress’ investigations—ignoring the long-standing interpretation of Article I, Section 8 of the U.S. Constitution, and a 1938 ruling by the U.S. Supreme Court that said “A legislative inquiry may be as broad, as searching and as exhaustive as is necessary to make effective the constitutional powers of Congress.” This is why people are nervous about the endurance of our system of checks and balances. It’s why commentators are talking about the rule of law. It feels under assault. The fact that the president who campaigned in the language of a would-be king (“I alone,”) is defending executive prerogative seems unsettling.

But we have to acknowledge that Donald Trump is not the first president to resist Congressional investigations. As Michael McConnel noted in a thoughtful op-ed in The Washington Post, the Obama administration fought Congressional investigators in the “Operation Fast and Furious” case involving then-Attorney General Eric Holder. President George W. Bush refused to cooperate with a Congressional investigation of his decision to fire nine U.S. attorneys in 2006. Even President George Washington refused to share documents from his administration relating to the rout of Army forces by a force of Native Americans in present-day Ohio in 1791. In most cases, Congress seeks information and the executive branch resists and after some negotiation and accommodation, both branches of government are able to fulfill their constitutional duties.

This is the essential nature of divided government as enshrined in our Constitution, defended in Federalist #51, and celebrated for more than 2 centuries. The branches of the federal government—the legislature, the executive, and the judiciary are co-equal branches of government.

In Federalist #51, Madison explains that the three branches of government were constructed by the founders to rival each other for power. “Ambition,” Madison wrote, “must be made to counteract ambition.” The Founders were worried, principally, about the accumulation of power in any one branch of government such that conditions favorable to tyranny might arise. Their solution, divide the powers of republican government between the states and the federal government; then divide the power of the federal government between legislative, executive, and judicial functions into three co-equal branches of government. This is the three-legged stool we learned about in grade-school.

I am ever-mindful of the admonition that “eternal vigilance is the price of liberty,” and we, as citizens, have to be awake, and aware, and engaged. Congress has to conduct oversight. But executive branch resistance to that oversight isn’t new. And so I find myself, today, taking some comfort in the idea that our system is working—as unsatisfying as that may be for some. Yes, the system created by the founders is being tested, it’s being strained, but it is still working—as designed—230 years after it was created.