George H.W. Bush: A Personal Remembrance

Adjunct Fellow Ray Raymond writes a personal remembrance of President George H.W. Bush.

West Point 5 October 1994. It was a cold, grey rainy day. Former President George H.W. Bush was on post to receive the Academy’s highest honor, the Thayer Award. Established in 1958, the Thayer Award is given to an American citizen – civilian or military –whose contribution to protecting US national interests embodies West Point’s values of “Duty, Honor and Country.” Everyone on post was looking forward to honoring a beloved former Commander in Chief, a decorated World War II veteran. The one concern was whether the pouring rain would force the Superintendent Lt. General Howard Graves to cancel the parade in President Bush’s honor. Miraculously, just as the Superintendent was about to cancel the parade, the rain stopped and the sun broke through bathing West Point’s historic plain in a gentle Fall light.

I was there as a British diplomat, to represent Her Majesty’s government and to honor President Bush, a man I greatly admired. Aged 70, dressed in an elegant blue suit, the former President looked fit and trim. With his characteristic graciousness and humility he greeted me warmly and thanked me for coming. He seemed touched that a representative of the British government was there to honor him. Although I had worked on UK-US relations during his Presidency, it was my first time meeting President Bush in person. It was also the first of several meetings I was privileged to have with him in his post-presidential years.

What stands out in my memory was not only his personal kindness and graciousness, but also the strength of his convictions and the clarity of his vision expressed in his address to the corps of cadets accepting the award and in a cadet seminar the following morning. His analysis of the challenges likely to face the United States in the late twentieth and early twentieth century was prescient, his understanding of the fragility of the rules-based post-Cold War liberal world order was deep, his call for continued American global leadership passionate and convincing. President Bush said: “We face not the end of history but, rather, the march of history. Not the end of ideology but the resurgence of intolerant nationalism, religious fanaticism, and bloody ethnic strife fueled by the proliferation of deadly weapons and unrestrained terrorism.” As ever, President Bush was the consummate realist. He did not mean that the US should be the world’s policeman. Rather, he argued that the US should act “ as a sheriff offering to organize and lead the posse against international wrongdoers, but not shouldering the burden alone or defending others’ interests for them. The US should focus its diplomatic and military efforts only when US interests and value were at risk; where US leadership “could make the critical difference” and where there was a “high probability of success.”

The next morning President Bush led a seminar for cadets. One cadet asked him what he would have done if Congress had not given him authority to use force to drive Saddam Hussein out of Kuwait. Without hesitating for a second, President Bush replied that he would have launched military action anyway and challenged Congress to impeach him. There was the steely resolve that was so characteristic of President Bush when he was convinced that what he was doing was right.

As a British diplomat working on UK-US Relations, I had an unusual vantage point to observe President Bush’s diplomacy as he summoned the universe of his knowledge, experience and skill to deftly navigate the US and its allies through the biggest realignment in international politics since the end of World War II. This was a period of unusual danger and opportunity in which the Berlin Wall and the “Iron Curtain” fell, Germany reunified, Soviet Union collapsed, and Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait.

Britain and the United States have enjoyed a unique relationship since World War II based upon shared values and interests. The special quality of the alliance has been grounded in a shared vision of an open, democratic rules-based liberal world order that they built together after World War II. They have also had the ability to disagree on how best to implement it. As one US diplomat wrote of the “special relationship”: “It is our ability to disagree, to argue passionately, candidly and forcefully with each other – and then to pick up the pieces, place our anger behind us and go forward together-that makes the relationship special and explain why it has thrived. “

President Bush valued the “special relationship” highly. He once described it as “the rock upon which all dictators this century have perished,” referring to the joint role the two allies played in combating Nazism and Communism in the twentieth century. In dealing with the extraordinary international challenges from 1989 onwards, President Bush had a trusted but difficult ally in British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. She had had a long and intimate friendship with President Ronald Reagan, that had begun years before either of them was elected President or Prime Minister. They were ideological soul-mates: both fierce anti-communists, robust champions of free markets and free trade. President Bush shared these values although he was never an ideologue. But he and Mrs. Thatcher did not share a pre-existing friendship and I had the impression that cocooned in her unique relationship with President Reagan she neglected to cultivate George Bush as much as she should have done.

Diplomacy requires tact, discretion, courtesy, graciousness, high intelligence and the ability to build lasting relationships of trust. Gorge H.W.Bush had all of these qualities in abundance. He needed them to deal with Mrs. Thatcher who had become accustomed to lecturing and occasionally dominating Ronald Reagan. President Reagan always seemed comfortable with this. President Bush was not. He was determined to put his own distinctive stamp on US foreign policy and to execute it with his own quiet brand of personal diplomacy. George Bush and Margaret Thatcher respected and trusted each other, but the personal chemistry was never as strong as it had been between Reagan and Thatcher.

President Bush and Prime Minister Thatcher agreed that Mikhail Gorbachev was someone the West could work with to end the Cold War. They also agreed on the need for a resolute and if necessary a military response to Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait. But German reunification presented a greater challenge for the Bush-Thatcher relationship. To end the Cold War, President Bush understood that he had to solve the century-old “German question”. His solution was a reunified Germany within NATO. To that end, in partnership with West German Chancellor, Helmut Kohl, he set out the basic principles to integrate a reunified Germany into NATO and the European Community. At first, the idea of a reunified Germany appalled Mrs. Thatcher. Her formative experience had been 1940: Britain’s “finest hour” standing defiantly and successfully against Nazi Germany. I remember being tasked with identifying and inviting German experts at American Universities to a day-long seminar at Chequers, the Prime Minister’s country retreat, to help her understand the enormity of the threat posed by a reunified Germany. It took all of President Bush’s patient, personal diplomacy to persuade Mrs. Thatcher that a reunified Germany within NATO and the European Community was a prize worth winning.

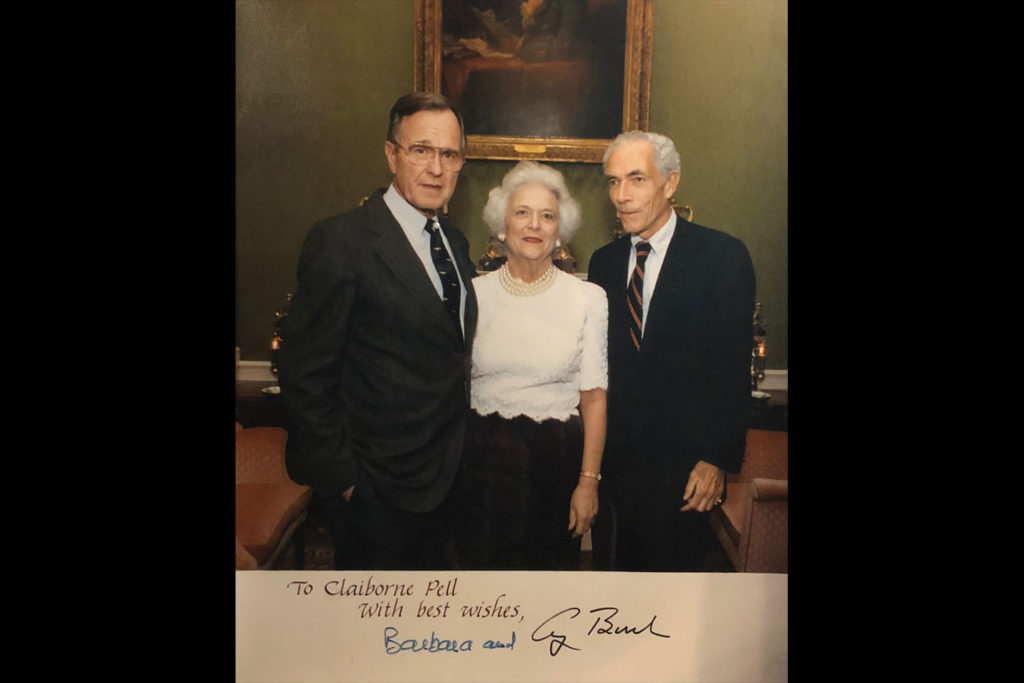

I mourn the passing of a great and good man, a master diplomat. Like Senator Claiborne Pell, George H.W.Bush was the kind of public servant America’s Founders hoped for : a man of principle, unquestioned and unquestionable integrity, humility and decency. Like Senator Pell, George H.W.Bush was a New England patrician with a profound sense of noblesse oblige. Above all, he was a visionary diplomat who steered the world through the biggest and most dangerous realignment of global politics since the end of the Second World War. I fear we may not see his like again.