Picks of the Week: Creeping Authoritarianism

The Governing Cancer of our Time | The New York Times

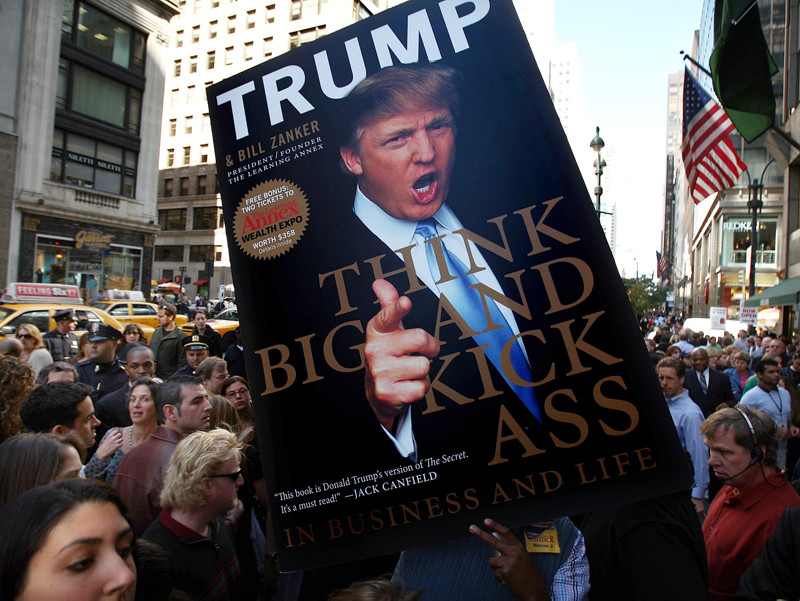

The best predictor of Trump support isn’t income, education, or age. It’s authoritarianism. | Vox

More than five years ago in The Providence Journal, I wrote of a specter haunting America. Then I was concerned about impatience on the left of the political spectrum and my growing sense that authoritarianism was gaining in popularity. I repost those views this week in light of the rise of a clearly authoritarian candidate to prominence in the Republican party.

It doesn’t matter what your political perspective—politics is essential to democracy. You can disagree with the compromises that are made, but it is the best process humanity has created to govern.

In the U.S., the lure of authoritarianism

Originally published in The Providence Journal, October 20, 2011

There is a specter haunting America—the specter of authoritarianism. It is not yet mainstream, but it is creeping into mainstream discussions about fixing Washington’s broken politics.

To be clear: there is a crisis in our democracy. Our governing system, strained by partisanship and poll-watching, has lost its ability to tackle difficult issues. Instead of leadership from any corner, we find a palpable desire, especially in Congress, to pass the buck, to avoid responsibility, and, as a result, to avoid issues of importance.

The result is a dysfunctional political process that looks paralyzed.

For those who believe that government is the solution, if it would only get out of its own way, the temptation to dismiss democracy as a hindrance can be overwhelming.

Such instincts, though are not only misguided, they are dangerous and should be repudiated immediately and emphatically.

Take for example Peter Orszag, the former Director of the Office of Management and Budget in the first 18 months of the Obama Administration. Writing in The New Republic, Orszag said,

To solve the serious problems facing our country, we need to minimize the harm from legislative inertia by relying more on automatic policies and depoliticized commissions for certain policy decisions. In other words, radical as it sounds, we need to counter the gridlock of our political institutions by making them a bit less democratic.

But he’s not alone. James Hansen, of NASA and Columbia University, wrote late last year with an unabashed admiration for the way in which China’s brand of authoritarianism makes it possible for that country to lead on an important (and real) issue like climate change:

I have the impression that Chinese leadership takes a long view, perhaps because of the long history of their culture, in contrast to the West with its short election cycles. At the same time China has the capacity to implement policy decisions rapidly. The leaders seem to seek the best technical information and do not brand as a hoax that which is inconvenient.

Of course admiration for a government’s responsiveness to big issues is a far-cry from advocating constitutional change—but it is a slippery slope. And it is one that Americans have stepped onto time and again when difficult challenges have arisen. Recall the adulation given to German economic progress in the 1930s, or the envy of Soviet achievements in space and science in the late 1950s.

The current appeal of technocratic authoritarianism is best exemplified in the struggle to get America’s national debt under control.

In recent years we have heard both Democrats and Republicans propose a statutory budget commission whose recommendations would, in effect, have the force of law.

A statutory commission with such sweeping authority is not unprecedented. For several decades, Congress has relied on this model to close excess military bases. After study and review, the commission makes its recommendations. If a resolution of disapproval is not passed in both houses of Congress in a certain period of time, the recommendations take on the force of law.

It’s an ingenious device. Public comment periods built into the process provide members of the House and Senate the opportunity to posture and pontificate while knowing they will never have enough votes to stop the process from proceeding.

It’s also a complete abdication of constitutional responsibility. Instead of grappling with great and difficult issues, members of Congress cede the authority vested in them by the Constitution to a panel of unelected, unaccountable oligarchs.

In the case of a statutory deficit commission, Congress would be abandoning the principle of self-rule—authority over our own taxes and our own expenditures—that inspired our founders to seek independence from Britain 235 years ago.

We should not be seduced by an expedient solution that is inconsistent with our form of government and dangerous to our Constitution. If we conclude that our elected representatives are unable to decide what we should pay in taxes and what we should spend on programs, then someone will soon ask “What do we need them for?”

The challenges facing the United States are not too big to solve. Nor is the United States too big to fail. Leaders have to lead and accept the electoral consequences of their actions. Anything less leads to paralysis or, worse, a diminished democracy. – Executive Director Jim Ludes